I wonder what’s different.

The transportation for one. Greyhound no longer brings their gargantuan buses this far up Vancouver Island, and as we careen down the narrow two-lane road with six inches of shoulder, I can see why. The playlist blasting in my ears has changed, though I brought back some classics like Death Cab for Cuties’ Bixby Canyon Bridge and Snow Patrol’s Make This Go on Forever.

A myriad of greenery blurs outside the window. I watch these forests differently, too. Oh, my heart still flutters at the boughs of red cedar hiding secret pathways to 6,000-foot peaks. But I also see acres of young hemlocks scrunched together like matchsticks in neat little packages. Phrases like “stem exclusion” and “30-year harvest cycles” whisper with sullen voices. Countless watersheds line the east side of Vancouver, but the Tsitika River I just rumbled past is the only one that hasn’t been logged. Tsitiaka winds through the tallest mountains on the Island and reaches saltwater at a little place called Robson Bight.

Orcas. It always comes back to orcas.

For two days, I have ferried, flown, and ridden from Gustavus to Juneau to Seattle to Victoria and am now just an hour from Port McNeil. Despite my evolving playlist and old-growth forest opinions, it still feels impossible that my first trip to Port McNeil was 17 years ago. Surely it was just a couple of weeks ago that I hopped off the Greyhound. Wasn’t it last weekend that I drove a Nissan Pathfinder up this road with a cat and rabbit in the back seat?

These roads, islands, and waterways hold a lot of the stories and experiences that explain the evolution from basketball boy to kayaker, guide, naturalist, bum, redneck-hippy, writer, conservationist, and whale aficionado. I’m counting on it providing a few more.

Ferried. Flown. Ridden.

I count the number of petroleum-driven vehicles that propelled me from Gustavus to the footsteps of Port McNeil, Johnstone Strait, and my precious Hanson Island. All to go on one more monkish retreat in the woods and waters of my youth. All to catch one more ride on a boat powered by an outboard motor or go paddling in a kayak made of, you guessed it, fossil fuels.

Too small to tip elections in favor of Mother Earth, I run to my favorite hiding place, sheltered by, you guessed it, Mother Earth.

If the trees are passing judgment on my life choices, they keep it to themselves. If those replanted hemlocks are packed like matchsticks, what happens if one of them lights? I woke to the news that California was burning during the wet season. A world getting drier, warmer, crazier, more unpredictable. Surely, it would be the earthquakes that doomed southern California. We beat San Andreas Fault to the punch.

***

Don’t cry. Whatever you do, don’t cry.

All those old names:

Blackfish Sound, Pearce Passage, Weyton Pass, Blackney Pass, Queen Charlotte Entrance.

Bold Head and Cracroft Point. Blinkhorn Peninsula and Kaikash Creek.

I know them all, have stared covetously at their little faces for eight years, promising I’d see them again. I’m sure they’ve been getting on just fine without me.

I confess I left my guilt on the Port McNeil dock, catching one more 45-minute ferry ride to Cormorant Island and the town of Alert Bay—the end of public transportation. I wait two days for a weather window that finally comes as low pressure turns to high and the wind pivots from southeast to northwest.

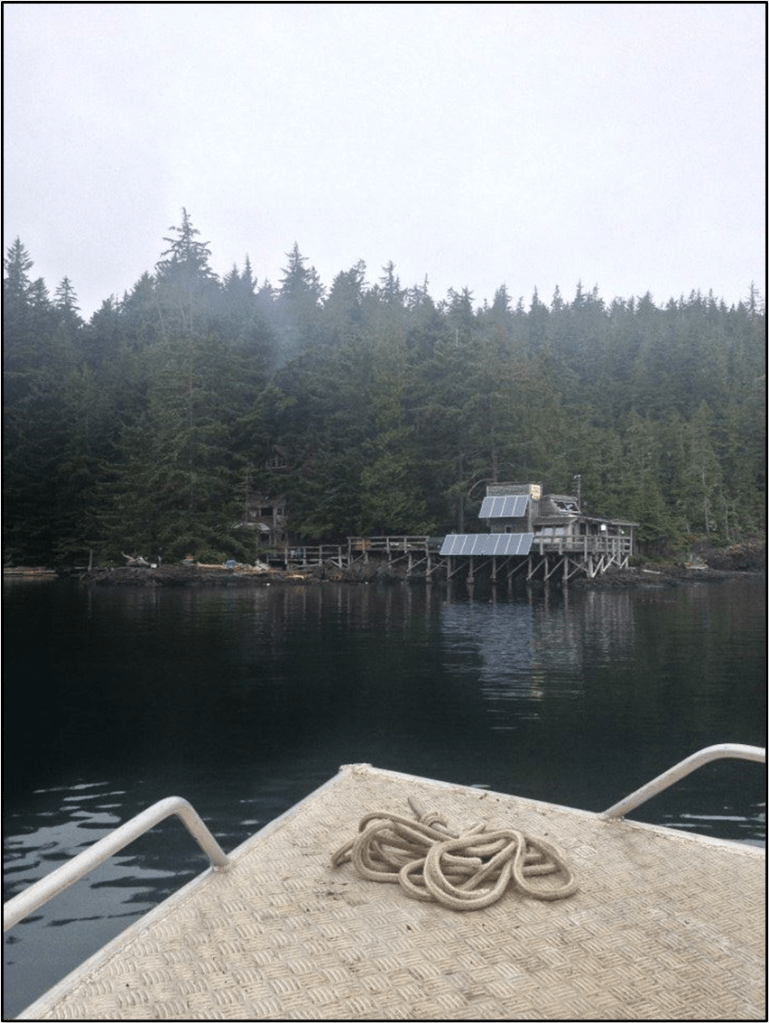

Every town run from Orca Lab to Alert Bay took me past Double Bay, its long boardwalk, floating dock, and cherry red rooftops. I shoulder my pack and follow the other caretaker, Laurene, up the dock. She directs me to a cabin on the right side of the horseshoe-shaped boardwalk, perched on the rocks with a view of Blackfish Sound and the first layer of the Broughton Archipelago’s islands.

The door opens, and the pack thumps from my shoulders. The cabin is bigger than my Gustavus design, with a half-loft upstairs, a functional shower, even a flush toilet. I would have settled for half-a-shabin and a cot. It’s not the high-end amenities that made the pack fall.

Don’t cry. Whatever you do, don’t cry.

Next to the kitchen table is a shelf. On it rests a radio receiver that looks all too familiar. Whether donated or purchased from Orca Lab, the ocean blares from the speakers—water gurgling, a distant boat engine, crackling shrimp. I swear I hear A pod.

“We have a hydrophone at the mouth of the cove,” Laurene explains, unaware I have been transported back in time. “There’s a volume knob on the right—”

“I know,” I interrupt. Not the best first impression.

I cross the room and crank the volume. How many nights did I fall asleep to this? She leaves me to unpack. I move quietly across the floor as if I’m in church. Clothes upstairs, tortillas and cheese in the fridge. Curry paste in the cabinet. I open the wood stove and smile. A pile of ash has calcified on the bottom and shrunk the stove’s space in half—a chronic problem with burning wood soaked in saltwater.

I pry the ash free and grab a handful of piled kindling. With eyes closed, I bring a stick of red cedar to my nose and inhale like an addict, listening to the hydrophone as my head spins and heart palpates. Our sense of smell pales in comparison to most mammals. Yet its ability to conjure memories is undisputed.

There is a smell to Hanson Island I have found nowhere else. Something in the ground, the water, the trees. Perhaps it’s as simple as it remains one of the few islands in the region that has not been clear-cut. Old-growth smells for a land that measures lifespans in centuries and seasons in seconds.

***

I weave between cedar and fir, balance on fallen skyscraper hemlocks, and plunge through salal undergrowth. I squish deer scat between fingers and spy on harlequin ducks perched on rocky beaches. Rumor has it a wolf has taken up residence on Hanson Island. I scan the hills with blind optimism for hazel eyes, ears cocked for the howl that proclaims that there are still things green and wild and true on this burning planet.

The rising northwesterly brings the forest to life with creaks and cracks. I settle against the hollowed-out trunk of a cedar, its innards charred from a long-ago lightning strike. Yes, even here, there can be fire from time to time. The stubborn cedars simply refuse to rot and fall, standing even in death in defiance of the decay and rebirth that comes for all.

I scratch at the charred bark and sniff. Any smell of fire is gone. The forest around me vibrant and healing. I watch the treetops, content to let the afternoon crawl away. There will be time tomorrow to check in and learn what is expected of me here, how I can give back to this place that dreams of becoming a sanctuary and educational retreat. It took enough petroleum to get me here. I will live, write, and eat in a shelter made of wood. I’ll try to leave this place better than I found it.

Wet earth soaks into wool pants, a pleasant shiver travels up my spine. Ravens cackle, eagles retort. Somewhere, an orca explodes to the surface. I feared two months wouldn’t be enough time to find what I was looking for. But as eyes close and my soul rises to the island’s tallest canopy, I know it’s already been found.