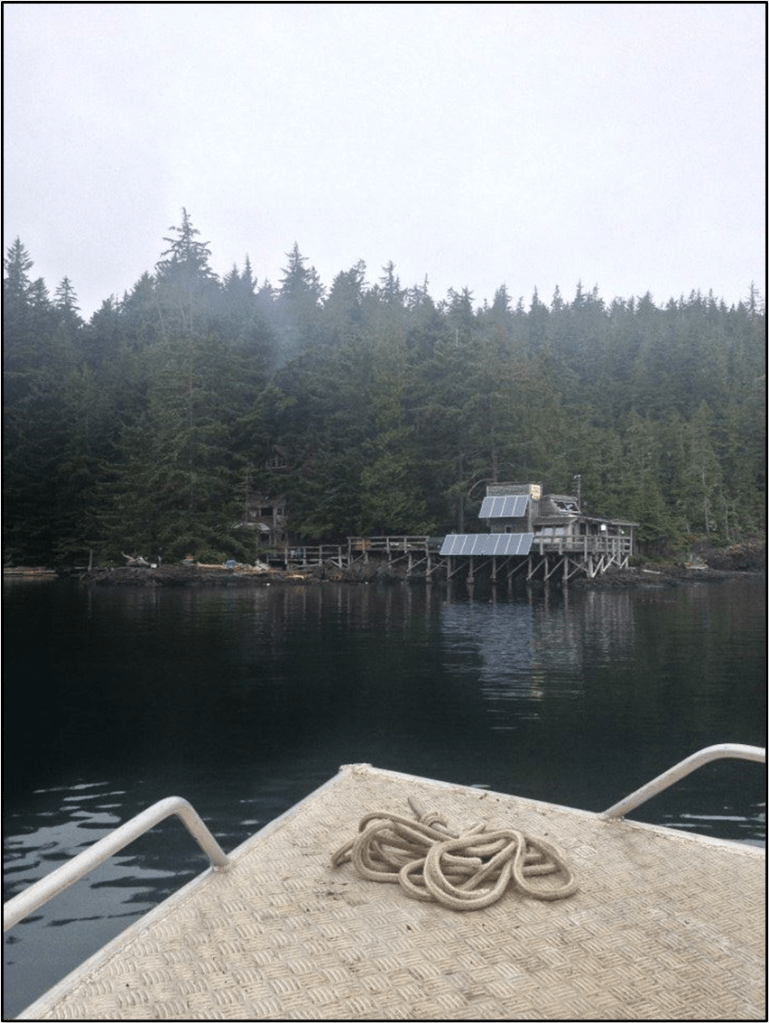

The zodiac skims across the water, the wind whips, and the disturbed water leaves a frothywhite “V” behind us. Another fjord. Tall stately mountains border a wide drainage at the head of the bay. Squint your eyes and it could be Mud Bay, Idaho Inlet, or any number of classic southeast Alaska drainages lined with bears awaiting the salmon. But those rivers are 8300 miles away.

I have gone to the other end of the globe… to see glaciers. To see a land defined by ice and the frenetic and beautiful artwork they had carved. There are no bears here in the fjords of Patagonia. Though there are rumors that a puma or two occasionally makes its way down to the island of Tierra Del Fuego. Nor are there spruce or hemlock forests. Instead southern beech trees coat the shorelines and stretch up toward the alpine.

Despite being at roughly the same latitude as north Vancouver Island, the fjords of Patagonia feel more like the Aleutions than they do the Pacific Northwest. It’s the price paid for a ceaseless wind that whips across the south Pacific with nothing between New Zealand and Chile to slow it down.

Despite being 200 yards from the beach, the zodiac slows. I glance down to see mud beneath a couple feet of water. The long tide flat stretches deep into the fjord. Our landing may be more of a “storm the beaches” situation.

“Uno, dos, tres, quatro, cinco, seis, siete, ocho…” sings out Javier from behind me.

I scan the shoreline. What’s he counting? I bring the binoculars to my eyes and train them on a massive boulder just above the waterline. That’s no rock. That’s an elephant seal. But… it can’t be. It’s too big to be anything that lives, breathes, and moves on land without being crushed uner its own weight.

The zodiac can’t go any further. We splash over the side, holding bins for life jackets and other pieces of gear over our heads. In 30 minutes the guests aboard the National Geographic Explorer would be deposited on the beach, awaiting the quirky, entertaining, and informative knowledge of these skilled and capable naturalists that know the land so well.

A little secret, I’ve never been here before. Hadn’t set foot in South America, let alone Patagonia before a couple days ago. And there’s only so much one can absorb from books and documentaries before your Xtra-tuffs hit the beach. I’d joked about Patagonia just being “Alaska with penguins,” but it wasn’t.

This was a wild, crazy country. A place humans had no business living. The wind. It blows constantly. Not a gentle breeze, but 40, 50, 60 knots with storm tossed waves that make the boat pitch and roll on every ocean crossing, sending me bouncing out of my bunk and water bottle clattering off the table. The plants were unfamiliar, the mountains held glaciers, but the inlets and bays were foreign. Even the dolphins and porpoises felt like strangers. With a pang I realize I’m homesick.

I lug the bins up the beach. The boulder turns, a grotesque snout flopping over its open mouth. It lets out a bellow that echoes off the mountains and thunders up the valley. The male elephant seal is massive. 4500 pounds easily. And we’re walking right past it. My fellow naturalists barely spare it a glance. Decades in the Alaska woods has trained me that anything this large should not be approached under any circumstances. Yet here we were. Trying to fit in I follow in Javier’s footsteps but can’t resist giving the monster a wide berth.

I have stepped into Jurassic Park. The elephant seals are scattered across the mile wide beach. Females and pups cluster in groups while males wallow closer to the water, allowing the flooding tide to cover them up until only their snouts are exposed. The roars of the males and barks of the pups sharply ring out on the still, clear morning.

In theory I should be “scouting” the three-mile long hike up the valley I was tasked with leading. But I can’t step away from the elephant seals. I perch on a rock and look down on a small cluster of females and pups. My eyes land on one pup pressed against his mothers belly and vibrating gently. He’s nursing, latched on tight and chugging away.

A nearby male gives another roar. How on earth could this fluffy gray thing turn into that Jabba the Hutt wannabe? I hadn’t given much thought to elephant seals when I was offered the two week Patagonia contract. But now that I was here… there was something so peaceful, so grounding about these massive animals. I slip into a meditative state and let the world and everything in it slip away.

These seals spend 90% of their life in the ocean. It was special to catch them on the beach like this. In their tenderest, most intimate moments they make landfall to give birth and nurse before setting out for months of traveling and foraging. The pup has no idea that his blissful little existence has an expiration date. In just a few short weeks, mom will leave him at the mercies of the ocean. No more milk made up of 40% fat to sustain him. He’ll have to head for open water where food dives deep and orcas lie in wait.

He doesn’t want to leave this beach. As homesick as I am, neither do I. For five weeks I have explored the deep woods of British Columbia and fantasized about kayak trips that varied from weekend getaways to starting in Seattle and not stopping until I saw Margerie Glacier. I’d flown to the other side of the world to see some of the most beautiful and dramatic fjords on earth. Alaska is gorgeous, but it doesn’t make glaciers the way they do down here.

Things would change rapidly for me and that little pup. But at some point, we’d have to wiggle over those drift logs, hit the water, and keep on swimming.

The sound of an outboard wraps around the point. Right, there are people coming. I was supposed to find a trailhead. I scurry off the rock, leaving the pup to suckle and enjoy the sunshine that has finally crawled above the highest peak. In my mind I review the list of plants, birds, and stories I have learned. The list was growing every day, and luckily most of the flora and fauna had, “southern, Antarctic, or Magellanic” in its name. One could simply point at a clump of grass and declare with some authority that it was “Antarctic grass.” Not that I would ever.

The zodiac approaches, the elephant seals roar in greeting, and an Andean condor rides the thermals far above. The southern wind slams against my face, I close my eyes, taste salt, and revel in the unknown, the unexplored, and the prospect of following that pup into deeper water.