Finding relics is hard on this coast. The rainforest is tenacious, hungry, and unrelenting. It devours anything made of wood, eager to absorb it back into the ground and turn it into mulch so the next generation of trees can grow, topple, and repeat. Abandoned houses quickly crumble as their metal roofs rust and fall away. Even cast iron and the alleged “stainless” steel can only resist the pounding rain and ever-present dampness for so long.

So, walking through a place like the U’Mista Cultural Center in Alert Bay feels like something of a miracle. Referred to by the Namgis First Nations elders as a “box of treasures” the museum is chock full of regalia, masks, and artifacts, some of them of pre-contact vintage. Some are so precious that they have been given a special room where photography is forbidden. Stepping into this space with the same layout as a traditional Big House feels akin to walking into any holy place.

The big house in Alert Bay, British Columbia.

You can feel the age. Hear the whispers, the songs, the banging of drums on a stormy winter night while the wind howls up Johnstone Strait. For decades, potlatch ceremonies were forbidden by the Canadian government. The gatherings led to arrests and the confiscation of artifacts, language, culture, a way of life. It wasn’t until the Cultural Center was built that the regalia and masks were returned.

I kneel in front of an ornately carved orca, done in the classic form line design of the Pacific Northwest. The calls of the northern residents ring in my ears. Oral histories tell us that the “blackfish” swam in pods so thick that you could leap across their backs from one side of the strait to the other. Guess who likes the sound of that?

Black and white photos of old village sites, many long abandoned, run along the hallway. I know a lot of the names, or at least the ODWG (Old Dead White Guy) names of these islands and channels and coves.

Even after years exploring this coastline and probing the beaches, I know nothing about this place. So many remain just names on a map and nothing else. I thought that my wandering would be satisfied with that. That I could leverage my new life and travel wherever Lindblad was willing to send me.

A Patagonia contract looms. What are southern hemisphere glaciers like? Or humpbacks? Orcas? Do penguins smell as bad as everyone says they do? I’m intrigued, excited, thankful. But there’s a bungee cord tied to my heart. Any time I step too far from the B.C. coast, the cord goes tight and springs me back.

It has been six years since I hugged Paul Spong on the Alert Bay dock, promised to keep in touch, and boarded the ferry. 12 years since I first shouldered my pack and boarded a bus in Vancouver for the region that is my birthplace. The symmetry is not lost on me. All it took was U’Mista, an orca carving, and some black and white photos, to tell me that I don’t need to travel the globe to find myself. To be fed. To heal.

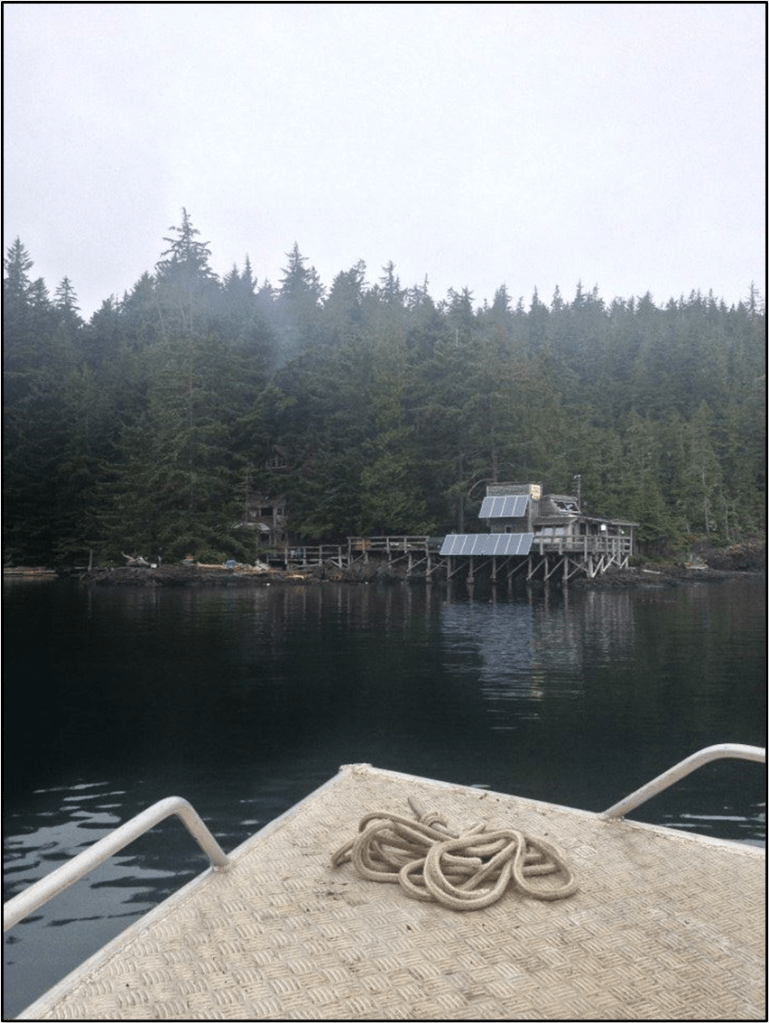

There are places where I have left beached my kayak, stepped into the woods, and felt a presence. Without fail, I would find evidence of human life.

A scarred tree where pitch has been harvested for fires. A strip of bark peeled from a red cedar. The miracle tree that could be lived under, paddled, and worn. A flattened divot where a house once stood. Wooden poles of an ancient purse seiner.

I step outside and look over the water. A southeast squall is rolling up the strait, but the rain has stopped and the sun bleeds through. I can see my wooden kayak rolling in those waves, battling the passage from Port McNeil toward Alert Bay.

This place is full of memories. Many beautiful, a few painful, others bittersweet.

But something it is abundantly clear. This place isn’t done with me. In what capacity or function I don’t know. The time has come to migrate back. To step into these woods I want to know, to feel that presence and sleep on that moss. Hear the wolves and watch the seals. Rivers and roads led me north, but at some point, in some capacity, I always knew they’d lead me back here.